Economists consider productivity—the economy’s output per each hour worked—a key ingredient in rising living standards. In our regular survey of news media, many—including at the Bank of Englandi —view productivity’s slow growth as a national scourge, limiting the economy’s future potential. However, in our view, productivity doesn’t foretell market direction or economic growth.

Divide gross domestic product (GDP, a government-produced measure of annual economic output) by total hours worked, and the result is what economists consider productivity. The Office for National Statistics tallies up UK GDP. It also counts all hours officially worked by everyone in the UK. If output rises more than hours worked, productivity increases. But if it takes longer to produce the same amount (or less), productivity falls. If productivity isn’t increasing, the popular theory goes, living standards can’t either because people would have to work more hours to consume more goods and services. Many also believe that if productivity is stagnant, wages and profits will be, too—since firms can’t sell more without raising costs. However, history shows productivity has never been the limiting factor these theories purport.

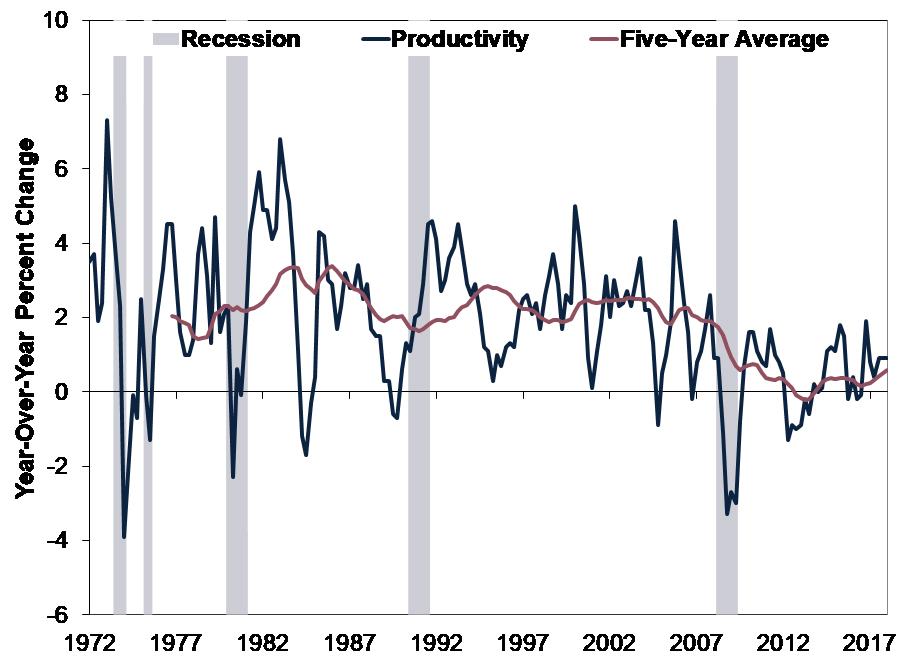

Low productivity isn’t a disaster. Over the last decade, whilst productivity growth is positive, its growth rate trails previous decades. To help illustrate productivity trends, Exhibit 1 shows year-over-year productivity growth and its five-year average. From 1972 to 2008, quarterly productivity growth averaged around 2.3% y/y.ii Since the last recession ended in June 2009, it has averaged only 0.5% y/y.iii But in our view, this doesn’t predict anything about future economic growth. Productivity growth often swings negative year-over-year, without causing recession, as Exhibit 1 shows. In 1984, 2004, 2012 – 2013 and 2015 – 2016, productivity growth was negative without an associated economic downturn. Moreover, although productivity’s five-year trend dipped negative in 2012 – 2013, UK economic growth persisted. And the trend is now rising, albeit still below its pre-2008 growth rate.

Productivity often grows fastest during and just after a recession, as companies respond to deteriorating economic conditions by reducing employee headcount. The need to keep costs low motivates them to do more with less, fostering large efficiency gains. During the past recession, the number of people employed fell far less than it did during the prior two recessions, as firms opted to weather the storm without dramatically reducing headcount.iv In our view, slower productivity growth since the recession stems largely from having a relatively higher denominator.

Exhibit 1: Past Productivity Isn’t Prelude

The reason productivity isn’t predictive is because its components—GDP and hours worked—aren’t. They measure past economic conditions, which are not predictive. Moreover, employment data—like hours worked—tend to be lagging economic indicators. Therefore, we think combining them doesn’t provide a clear view of the economic outlook, which is what markets care about. Productivity tells you only what happened in the past. However, in our view, markets are forward looking. We think they reflect likely events about 3 – 30 months ahead, with a particular focus on the next 12 – 18 months.

Also, there are flaws in how productivity is measured. A wide body of scholarly research has shown GDP as measured today isn’t entirely accurate accounting for services-driven global production. Official hours worked may also not square with reality, as it can omit certain self-employed hours. These statistics were born in the 20th century, when a larger share of output was physical goods, which are much easier to measure. Digital technology has multiplied consumption of items like music and photos, yet their share of economic activity has shrunk. Though digital products’ prices have exponentially declined, their use has skyrocketed—along with many communication services companies’ shares—but you wouldn’t see it in official GDP or productivity statistics.

Ultimately, we think markets care about future corporate profitability. Publicly traded companies’ productivity is an ingredient in this, but it isn’t the only input. Productivity is measured economy wide, including private businesses and partnerships—not all that relevant to public equities. Plus, productivity doesn’t account for wages and other costs like interest, rent and depreciation, so it isn’t too useful for figuring profitability. For example, despite crawling productivity growth last year, FTSE 350 corporate earnings hit record highs last year.v

Don’t get us wrong. Doing more with less—and in less time—is great! But for markets, productivity—as measured by the government—generally doesn’t tell markets anything they don’t already know or how productive the economy will be in the future. Low productivity growth doesn’t appear to be stifling the UK economy or markets.

Investment management services are provided by Fisher Investments UK’s parent company, Fisher Asset Management, LLC, trading as Fisher Investments, which is established in the US and regulated by the US Securities and Exchange Commission. Investing in equity markets involves the risk of loss and there is no guarantee that all or any invested capital will be repaid. Past performance neither guarantees nor reliably indicates future performance. The value of investments and the income from them will fluctuate with world equity markets and international currency exchange rates.

i“The UK’s Productivity Problem: Hub No Spokes,” Andy Haldane, Bank of England, 28/6/2018.

iiSource: Office for National Statistics, as of 13/8/2018. Output per hour worked, year-over-year, Q1 1972 – Q1 2008.

iiiIbid. Output per hour worked, year-over-year, Q3 2009 – Q1 2018. Recession dates based on the Office for National Statistics’ definition: “Two or more consecutive quarters of falling gross domestic product (GDP).”

ivSource: Office for National Statistics, as of 28/8/2018. Number of people in employment (aged 16 and over), 1971 – 2017.

v“Investors Miss out on Bumper UK Profit Haul,” Kate Beioley, Financial Times, 9/5/2018.